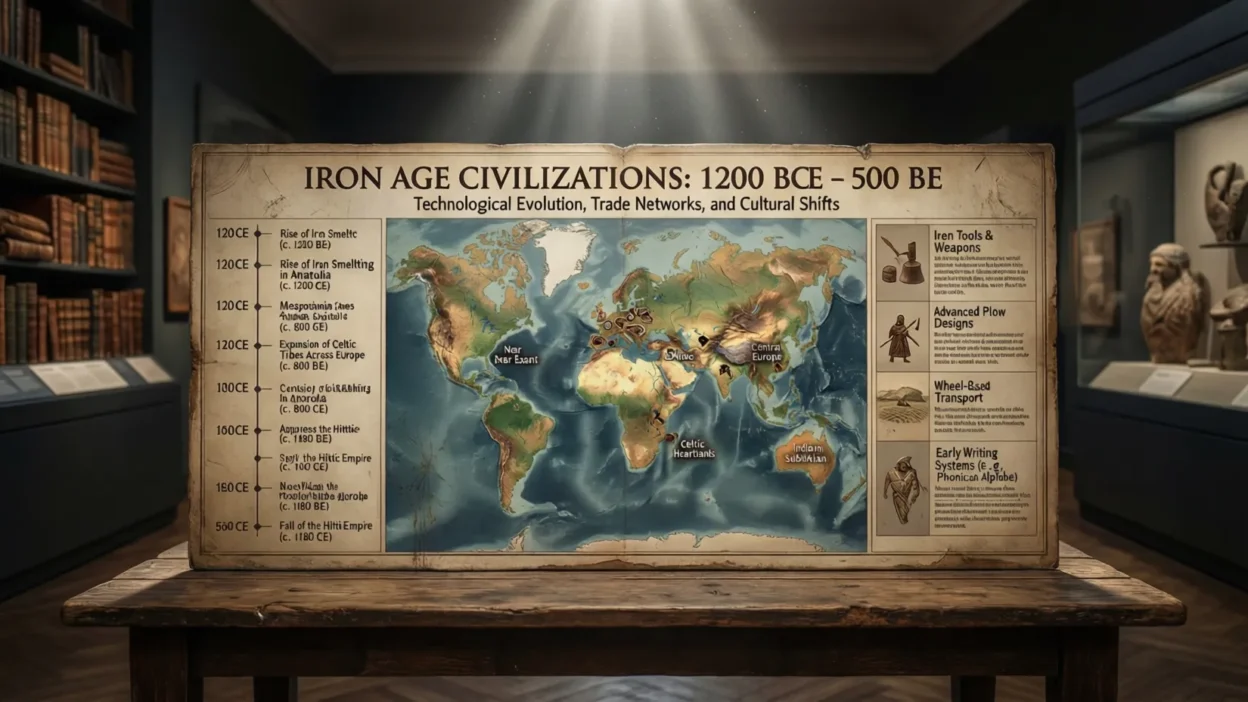

The Iron Age marks one of the most transformative periods in human history, defined by the widespread use of iron for tools, weapons, and everyday objects.

Emerging after the Bronze Age, this era did not begin at the same time everywhere, but generally developed between roughly 1200 BCE and the early centuries CE, depending on the region.

What set the Iron Age apart was not simply the discovery of a new metal, but the profound social, economic, and political changes that followed its adoption.

Iron was more abundant and durable than bronze, allowing communities to produce stronger tools, cultivate land more efficiently, and equip larger armies.

These advances reshaped daily life, encouraged population growth, expanded trade networks, and contributed to the rise of powerful states and empires.

By examining the technologies, societies, and cultures of the Iron Age, we gain deeper insight into how a single material helped lay the foundations of the ancient world and, ultimately, modern civilization.

Origins of Iron Technology

The origins of iron technology represent a critical turning point in early human innovation. Long before the Iron Age formally began, humans were familiar with iron in a rare and symbolic form: meteoritic iron. This naturally occurring material, fallen from the sky, was used as early as the third millennium BCE to craft small decorative or ceremonial objects. However, its scarcity prevented widespread use. The true breakthrough came with the development of iron smelting—the ability to extract iron from ore using high-temperature furnaces.

Unlike copper and tin, the metals used to make bronze, iron required significantly higher temperatures to smelt and sophisticated forging techniques to shape. Early ironworkers likely discovered these methods accidentally while experimenting with existing metallurgical processes. By around 1200 BCE, iron smelting had begun to spread in parts of Anatolia and the Near East, often associated with the Hittites, though modern research suggests the knowledge emerged gradually and independently in multiple regions.

At first, iron was not immediately superior to bronze; early iron tools were sometimes brittle or inconsistent in quality. Over time, however, blacksmiths learned to control carbon content and improve forging methods, producing stronger and more reliable tools and weapons. The abundance of iron ore compared to tin—an essential but rare component of bronze—made iron production more accessible. This accessibility allowed iron technology to spread widely, laying the technological foundation for the profound social and economic transformations that defined the Iron Age.

Chronology and Regional Timelines

One of the defining characteristics of the Iron Age is that it did not begin or end uniformly across the world. Instead, its emergence followed distinct regional timelines shaped by geography, resources, and cultural exchange. In the Near East, iron production appeared earliest, around 1200 BCE, during a period of widespread disruption known as the Late Bronze Age collapse. As major bronze-producing states declined, iron gradually replaced bronze as the dominant material for tools and weapons.

In Europe, the Iron Age began later, around 800 BCE, and is commonly divided into two major phases: the Hallstatt culture, characterized by early iron use and elite burials, and the La Tène culture, known for its advanced metalwork and distinctive Celtic art. These societies spread iron technology across much of the continent, influencing settlement patterns and warfare.

In South Asia, iron usage is associated with the later Vedic period, beginning around 1000 BCE. The adoption of iron tools supported agricultural expansion into forested regions, enabling population growth and the development of early states. East Asia followed a different path, with iron appearing in China by the 6th century BCE. Notably, Chinese metallurgists developed cast iron technology, which was largely unknown elsewhere at the time.

In Africa, particularly sub-Saharan regions, ironworking emerged independently rather than being adopted from the Near East. Cultures such as the Nok civilization demonstrate sophisticated iron production by the first millennium BCE. These varied regional timelines highlight the Iron Age as a global process shaped by innovation, adaptation, and cultural diversity.

Tools, Weapons, and Technological Advances

The widespread adoption of iron dramatically transformed technology during the Iron Age, particularly in the production of tools and weapons. Iron tools were stronger and more durable than their bronze predecessors, allowing for greater efficiency in agriculture, craftsmanship, and construction. Farmers benefited from iron plowshares, axes, sickles, and hoes, which made it easier to clear forests, cultivate heavier soils, and increase crop yields. These improvements supported population growth and more stable food supplies.

In warfare, iron brought equally significant changes. Iron swords, spearheads, arrowheads, and armor were not only tougher but also more affordable to produce due to the relative abundance of iron ore. This accessibility reduced reliance on elite-controlled bronze resources and enabled larger, better-equipped armies. As a result, warfare became more widespread and decisive, contributing to shifts in political power and territorial expansion.

Technological progress during the Iron Age also included advancements in blacksmithing techniques. Smiths learned to heat, hammer, quench, and temper iron to improve its strength and flexibility. Over time, they developed early forms of steel by controlling carbon content, greatly enhancing tool and weapon performance. Beyond agriculture and warfare, iron was used to create everyday items such as knives, nails, hinges, and household tools, improving daily life across social classes.

These technological innovations were not merely practical improvements; they reshaped economic systems, social organization, and patterns of settlement. Iron technology became a cornerstone of Iron Age societies, enabling the complex civilizations that followed.

Social and Economic Transformation

The introduction of iron technology triggered profound social and economic changes across Iron Age societies. As iron tools improved agricultural productivity, communities were able to produce food surpluses more consistently. These surpluses supported population growth and reduced dependence on subsistence farming, allowing more people to specialize in non-agricultural occupations such as metalworking, trade, and administration. The rise of skilled blacksmiths, in particular, elevated metallurgy to a central role within Iron Age economies.

Iron’s relative abundance compared to bronze reshaped economic structures. Since iron ore was widely available, communities were less dependent on long-distance trade for scarce materials like tin. This shift reduced elite control over resources and allowed broader segments of society access to durable tools and weapons. As a result, social hierarchies became more complex, with new classes of warriors, artisans, and merchants emerging alongside traditional elites.

Trade networks, however, did not disappear. Instead, they expanded and diversified. Iron tools and weapons were exchanged alongside agricultural goods, textiles, and luxury items, connecting distant regions through commerce and cultural interaction. Growing trade encouraged the development of markets and early forms of currency, strengthening regional economies.

Urbanization also accelerated during the Iron Age. Permanent settlements expanded into towns and cities, often strategically located near trade routes or fertile land. These urban centers became hubs of political authority, economic activity, and cultural life. Together, these social and economic transformations laid the groundwork for more centralized states and complex civilizations, marking the Iron Age as a decisive step toward the ancient world’s political and economic systems.

Warfare and Political Power

Warfare and political organization were deeply reshaped during the Iron Age, largely due to the widespread availability of iron weapons. Unlike bronze, which relied on scarce resources and elite-controlled trade networks, iron could be produced locally in many regions. This accessibility allowed larger segments of society to arm themselves, reducing the monopoly of warrior elites and transforming the nature of conflict. Armies grew in size, and warfare became more frequent and decisive.

Iron weapons such as swords, spears, and arrowheads were stronger and more durable, offering clear advantages on the battlefield. Defensive equipment, including iron helmets, shields, and armor, also improved soldier survivability. These technological advances encouraged new military tactics and formations, emphasizing discipline, coordination, and massed infantry rather than small elite forces. As warfare evolved, so too did political power.

Successful military organization enabled rulers to expand territory, protect trade routes, and extract resources through conquest or taxation. Iron Age societies increasingly developed centralized authority structures to support standing armies and sustained campaigns. This process contributed to the rise of powerful states and early empires, particularly in regions such as the Near East, Europe, and South Asia.

Beyond its practical use, iron carried strong symbolic significance. Weapons and armor became markers of authority, status, and legitimacy, often featured in royal iconography and burial practices. Control over iron production and military force reinforced political dominance and social order. Ultimately, the relationship between iron technology, warfare, and political power played a crucial role in shaping Iron Age societies and paved the way for the imperial systems of the classical world.

Culture, Religion, and Daily Life

Iron Age culture and daily life were deeply influenced by the widespread use of iron, extending far beyond tools and warfare. In many societies, iron acquired symbolic and spiritual significance, often associated with strength, protection, and transformation. Mythologies and religious practices sometimes linked iron to gods, ancestors, or supernatural forces, while iron objects were used in rituals, offerings, and protective charms. Burial practices frequently included iron weapons, tools, or ornaments, reflecting beliefs about status, identity, and the afterlife.

Art and craftsmanship flourished during the Iron Age, particularly in metalworking. Decorative iron objects, along with finely crafted jewelry made from gold, bronze, and other materials, demonstrate high levels of artistic skill. Distinctive artistic styles emerged in different regions, such as the intricate geometric and curvilinear designs of Celtic Iron Age art. These artistic traditions expressed cultural identity and reinforced social cohesion.

Daily life also changed in practical ways. Iron tools improved construction techniques, enabling stronger houses, fences, and infrastructure. Household items such as knives, cooking tools, and farming implements became more durable and widely available, enhancing living standards for many communities. Clothing production benefited from iron needles and shears, while improved agricultural tools reduced labor demands.

Gender roles and community organization varied widely across Iron Age societies, but economic specialization often shaped social responsibilities. Together, cultural expression, religious belief, and everyday practices reveal the Iron Age as a dynamic period in which technological innovation and human experience were closely intertwined.

Trade, Communication, and Interaction

Trade and communication networks expanded significantly during the Iron Age, connecting distant regions and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. Although iron ore was more widely available than the materials required for bronze, ironworking still depended on resources such as high-quality ore, charcoal, and skilled labor. This created regional centers of production that became important hubs within broader trade networks.

Iron tools and weapons were traded alongside agricultural products, livestock, textiles, pottery, and luxury goods such as jewelry and fine metalwork. Long-distance trade routes linked communities across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Near East, promoting economic interdependence and cultural interaction. Rivers, coastal routes, and overland paths played a crucial role in transporting goods and spreading technological knowledge.

Communication and interaction through trade also encouraged cultural diffusion. Artistic styles, religious beliefs, and social practices spread as merchants, craftsmen, and travelers moved between regions. Ironworking techniques themselves evolved through contact between societies, leading to regional adaptations and technological improvements. In some cases, trade fostered cooperation and mutual benefit; in others, it intensified competition and conflict over resources and strategic locations.

The growth of trade networks contributed to the emergence of marketplaces and early economic institutions, strengthening local and regional economies. Increased interaction between societies also accelerated political and cultural change, laying the groundwork for more complex social systems. Through trade and communication, the Iron Age became a period of heightened connectivity, shaping the interconnected ancient world that followed.

Environmental Impact

The technological and economic advances of the Iron Age came with significant environmental consequences. One of the most notable impacts was widespread deforestation. Iron smelting required large quantities of charcoal, which was produced by burning wood in low-oxygen conditions. As iron production expanded, forests were increasingly cleared to supply fuel, particularly near major smelting centers. Over time, this led to soil erosion, changes in local ecosystems, and reduced biodiversity in some regions.

Agricultural expansion also intensified environmental pressures. Iron tools allowed farmers to clear dense forests and cultivate heavier, previously unusable soils. While this increased food production and supported growing populations, it also transformed landscapes on a large scale. Fields, pastures, and settlements replaced natural habitats, altering water systems and wildlife patterns.

Mining activities further contributed to environmental change. The extraction of iron ore disrupted land surfaces and required the movement of large amounts of earth. In some areas, mining waste contaminated soil and water sources, affecting both human health and surrounding ecosystems. These effects were often localized but cumulative over centuries.

Despite these challenges, Iron Age societies were not entirely unaware of environmental limits. Some communities developed resource management practices, such as controlled woodland use or shifting cultivation, to sustain production over time. Nevertheless, the environmental impact of iron technology marked a turning point in human interaction with nature, reflecting the growing capacity—and cost—of technological power in shaping the natural world.

Comparison with Other Ages

The Iron Age is best understood when compared with the periods that came before it, particularly the Stone Age and the Bronze Age. During the Stone Age, tools were primarily made from stone, bone, and wood, limiting their durability and effectiveness. While stone tools were sufficient for hunting and basic agriculture, they restricted large-scale farming, construction, and warfare. Social organization during this period tended to be smaller and less hierarchical.

The Bronze Age introduced metalworking using copper and tin alloys, leading to stronger tools and weapons. However, bronze production depended on access to tin, a rare resource often obtained through long-distance trade. This scarcity concentrated power in the hands of elites who controlled metal supply routes, reinforcing rigid social hierarchies and centralized authority. Although bronze tools were effective, they were costly and limited in availability.

Iron ultimately surpassed bronze because of its abundance and adaptability. Iron ore was far more widely available than tin, allowing communities to produce tools and weapons locally. Over time, improved ironworking techniques resulted in tools that were stronger and more durable than bronze. This accessibility reduced elite monopolies over technology and enabled broader participation in agriculture, craftsmanship, and warfare.

Rather than representing a complete break from earlier periods, the Iron Age built upon existing knowledge of metallurgy and social organization. It combined technological continuity with significant innovation, resulting in deeper social complexity, expanded economies, and stronger political structures. These qualities distinguish the Iron Age as a pivotal stage in human development.

Decline and Transition to Historical Periods

The end of the Iron Age did not occur suddenly or uniformly, but instead marked a gradual transition into historically documented periods across different regions. In many parts of the world, the Iron Age faded as societies developed writing systems, complex administrations, and large-scale states that left extensive historical records. This shift is often associated with the rise of classical civilizations such as Greece and Rome in Europe, the Han Dynasty in China, and powerful kingdoms in South Asia.

Rather than a decline in technology, the transition reflected increasing political and social complexity. Iron tools and weapons continued to be used and improved, forming the technological backbone of emerging empires. Advances in steel production, infrastructure, and military organization built directly on Iron Age innovations. Roads, fortifications, and urban planning expanded, supported by iron-based tools and engineering techniques.

Within Europe, the Roman conquest absorbed many Iron Age societies into a broader imperial system, integrating local cultures into centralized political and economic structures. In East Asia, the consolidation of power under imperial dynasties transformed regional Iron Age cultures into unified states governed by bureaucratic systems. In other regions, Iron Age traditions persisted longer, blending gradually with early historical developments.

The transition from the Iron Age to recorded history marks a crucial threshold in human development. It represents the moment when technological innovation, political authority, and cultural expression became increasingly documented, allowing historians to trace the evolution of civilizations in far greater detail than ever before.

Legacy of the Iron Age

The legacy of the Iron Age is deeply embedded in the foundations of human civilization and continues to influence the modern world. One of its most enduring contributions was the establishment of ironworking and early steel production as central technologies. Techniques developed by Iron Age blacksmiths—such as forging, tempering, and controlling carbon content—formed the basis of later metallurgical advancements that remain essential to industry today.

Socially and politically, the Iron Age reshaped patterns of power and organization. The widespread availability of iron tools and weapons reduced dependence on scarce resources and helped democratize access to technology. This shift contributed to the rise of larger, more organized societies, enabling the formation of states, legal systems, and professional armies. Many political and social structures that emerged during this period influenced the administrative frameworks of later empires and nations.

Culturally, the Iron Age left a rich heritage of art, craftsmanship, and belief systems. Regional identities expressed through metalwork, settlement design, and ritual practices shaped cultural traditions that persisted long after the period ended. Iron also became a powerful symbol of strength, resilience, and progress in human imagination, reflected in myths, literature, and historical memory.

Ultimately, the Iron Age represents a turning point in humanity’s ability to transform the natural world through technology. Its innovations laid the groundwork for classical civilizations and the industrial societies that followed, making it one of the most significant periods in human history.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Iron Age

When did the Iron Age begin and end?

The Iron Age did not have a single start or end date. In the Near East, it began around 1200 BCE, while in Europe it started closer to 800 BCE. In some regions, Iron Age traditions continued well into the first centuries CE, gradually blending into historically recorded periods.

Why was iron more important than bronze?

Iron was far more abundant than the tin required to make bronze. This made iron tools and weapons cheaper and more accessible, allowing wider segments of society to benefit from improved technology and reducing elite control over metal resources.

Were Iron Age tools always better than bronze tools?

Early iron tools were not always superior to bronze. Initial iron objects could be brittle or poorly made. Over time, however, advances in forging and early steel production made iron tools stronger, more durable, and ultimately more effective.

Did all regions learn ironworking from the same source?

No. While iron technology spread through trade and cultural contact in many regions, evidence suggests that iron smelting developed independently in places such as sub-Saharan Africa. This highlights the innovative capacity of different societies.

How did the Iron Age affect daily life?

Iron improved farming, construction, and household activities. Stronger tools reduced labor demands, supported population growth, and improved living standards. Iron also influenced art, religion, warfare, and social organization.

Why is the Iron Age still relevant today?

The Iron Age laid the groundwork for modern metallurgy, state formation, and technological progress. Many systems central to contemporary society—industrial tools, infrastructure, and political organization—trace their origins back to this transformative period in human history.

Conclusion:

The Iron Age stands as one of the most influential periods in human history, marking a decisive shift in how societies organized their economies, technologies, and systems of power.

More than simply an age defined by a new material, it represented a fundamental transformation in the relationship between humans, resources, and the environment.

The widespread use of iron enabled stronger tools, more efficient agriculture, and more effective weapons, which together reshaped daily life and long-term historical development.

Through iron technology, communities expanded into new landscapes, supported growing populations, and formed increasingly complex social and political structures.

Trade networks widened, cultures interacted more frequently, and innovation accelerated across regions.

Although the Iron Age followed different timelines around the world, its impact was global, influencing civilizations from Europe and Africa to Asia.

The period also revealed the costs of progress, including environmental strain and intensified conflict, highlighting the dual nature of technological advancement.

The legacy of the Iron Age is still visible today. Modern metallurgy, industrial tools, and even contemporary political systems trace their roots to developments that began during this era.

By studying the Iron Age, we gain valuable insight into how innovation drives social change and how human societies adapt to new technologies.

Ultimately, the Iron Age reminds us that a single breakthrough—when widely adopted—can alter the course of history and shape the foundations of the world we live in today.

Jonathan Bishopson is the punmaster-in-chief at ThinkPun.com, where wordplay meets wit and every phrase gets a clever twist. Known for turning ordinary language into laugh-out-loud lines, Jonathan crafts puns that make readers groan, grin, and think twice. When he’s not busy bending words, he’s probably plotting his next “pun-derful” masterpiece or proving that humor really is the best re-word.